Hello, dear readers! This is an article I wrote for Jane Austen’s World that I knew you’d want to read. If you’ve ever wanted to know more about how Jane Austen’s heroines spent their mornings, this is for you!

I find Jane Austen’s daily routines inspiring, don’t you? She was well-rounded and enjoyed a variety of activities to keep her body, mind, and spirit healthy and balanced. She wrote newsy letters, played the pianoforte, prayed with her family, sewed beautifully, and loved brisk walks. Austen’s evenings at home were spent reading, sewing, and talking with her family. Evenings in company meant dinners, game tables, and dancing. And Sundays were set aside for rest and church.

But what else did Austen understand about the everyday lives of Regency women that might help further our enjoyment of her novels? What went on behind (and between) the scenes we love so well? In this series, I’ll cover a variety of topics on Regency women. Let’s start by looking at what women did each morning on a normal day.

Mornings

The Regency day was broken into two parts: Morning and Evening. Morning usually refers to the part of the day before dinner. Women changed their dresses for dinner, marking the evening portion of the day. Thus, when we read Austen’s novels, we must understand that “morning” encompasses what we refer to as morning and afternoon.

Pre-Breakfast: This was the time between rising and breakfast, which was given to various private pursuits and personal hygiene. A married woman or mistress of the house (as in Emma’s case) might use this time to look over menus and address household necessities with a housekeeper or servant. We know Austen used that time to practice the piano, walk in the garden or run short errands, and write letters to friends and family members. It’s easy to see that a lady’s personal time before breakfast was quite pleasant.

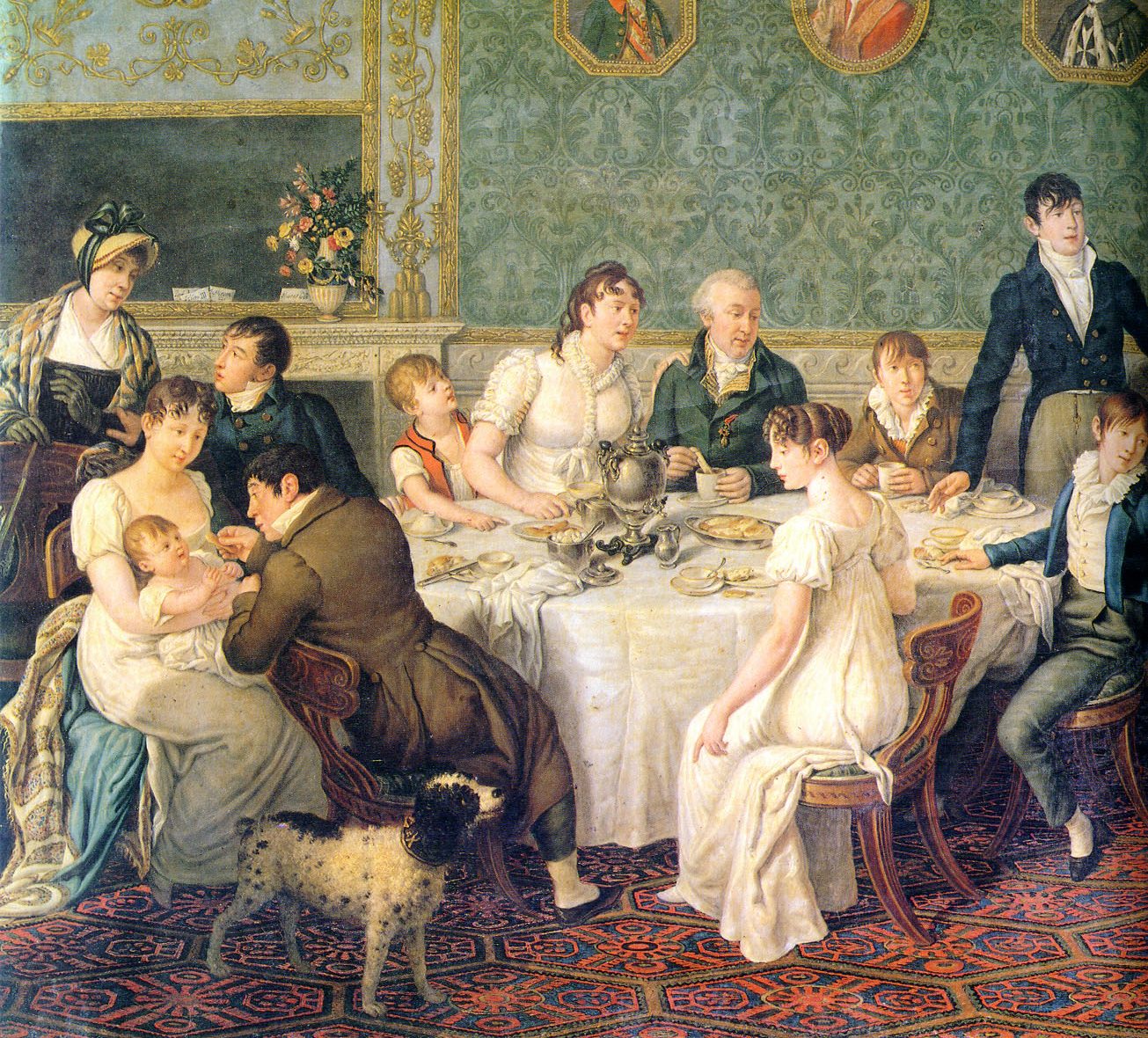

Breakfast: Breakfast was eaten around 10 a.m. in most households, as the Middletons and their guests do in Sense and Sensibility before their morning outing, though people in the country tended to eat earlier than those in town. Jane Austen herself was known for eating an earlier breakfast at 9 a.m. Breakfast was a leisurely meal, with food on the side board where people might serve themselves. In London at Mrs. Jennings’ table, we read that breakfast “lasted a considerable time” as it was her “favourite meal.”

Breakfasts in the Regency period were “dainty meals of varieties of bread, cake and hot drinks, served in the breakfast-parlour…and eaten…off…fine china” (Maggie Lane, Jane Austen and Food). However, an early and more substantial breakfast might be taken before traveling a long distance. In Mansfield Park, Henry and Fanny’s brother eat a hearty breakfast before setting out early in the morning: “the remaining cold pork bones and mustard in William’s plate might but divide her feelings with the broken egg-shells in Mr. Crawford’s.”

Coffee, tea, and chocolate were the favorite hot drinks of the time, but tea was a breakfast staple for the Austen family: “Toast was made in front of the fire by the consumers themselves, rather than by their servants” (Lane 31). Jane Austen’s duties at breakfast included “[t]oasting the bread and boiling the water for tea in a kettle.” In Sanditon, we find this detail: “[Arthur] took his own cocoa from the tray . . . and turning completely to the fire, sat coddling and cooking it to his own satisfaction and toasting some slices of bread . . .” (ch. 10).

Morning Calls: Visiting took up a great portion of the day, usually anywhere from 10 a.m. until 6 p.m., depending on each household’s meal times. Normally, it was safest to call between 12:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m. for most households. Between visits or on quiet mornings at home, women tended to sew together as we know Austen herself enjoyed doing. In Sense and Sensibility, we’re told that the ladies settled themselves after breakfast “round the common working table.” Their work, of course, was needlework.

Social visits were typically 15 minutes in duration. A shorter visit was considered a snub, as is seen in Emma when she allows Harriet Smith to make a 14-minute visit to the Martins: “The style of the visit, and the shortness of it, were then felt to be decisive. Fourteen minutes to be given to those with whom she had thankfully passed six weeks not six months ago!” (emphasis mine). However, in Pride and Prejudice, emphasis is given to the length of Georgiana Darcy’s visit to Elizabeth at the inn: “Their visitors stayed with them above half-an-hour” (emphasis mine).

Visits were made for a variety of reasons, but special visits to friends and neighbors were made before and after trips away from home; new neighbors were often visited, as we see in Pride and Prejudice when Mrs. Bennet pressured Mr. Bennet to visit Mr. Bingley; and new brides were visited by everyone in the neighborhood. When Mr. Elton brings Mrs. Elton home, Mr. Woodhouse says, “Not to wait upon a bride is very remiss. […] I ought to have paid my respects to her if possible. It was being very deficient.”

As a Regency woman, morning visits must have ranged from enjoyable and entertaining to downright bothersome and boring. But one thing we modern readers must keep in mind: Virtually every visit required a reciprocal visit. Once you began visiting someone, it must have been difficult to ever stop!

Luncheon: Lunch did not exist as we know it today. Instead, light refreshments were brought in during the day, often during visit. These light meals were comprised of cold foods and served in whatever room the family was in at the time. When callers came, the woman receiving a visit rang for refreshments and was expected to offer and serve tea and refreshments, all while carrying on polite conversation.

In Austen’s novels, these midday refreshments are referred to as a “tray,” “cold meat,” “a set-out” or a “cold repast” (Lane 35). In Pride and Prejudice when Elizabeth visits Miss Darcy at Pemberley, we read of “cold meat, cake, and a variety of all the finest fruits in season.”

Interestingly, the only time a “lunch” of sorts is mentioned in Austen’s novels is at an inn. In Pride and Prejudice, the Bennet sisters eat “‘the nicest cold luncheon in the world,’ which consists of ‘a sallad and cucumber’ and ‘such cold meat as an inn larder normally affords’” (Ch. 39). In Sense and Sensibility, Willoughby stops for a quick “nuncheon” when traveling from London to Cleveland, consisting of “a pint of porter” and “cold beef.”

Dressing for dinner: At the conclusion of a full day of visiting with friends, neighbors, and family members, Regency women then returned to their rooms to change for dinner. The timing of this change of dress again depended on the hours kept in each home. This provided women time to refresh themselves, arrange their hair, and put on their evening dresses. (I imagine they also took the opportunity to loosen their stays for a bit!)

Evening activities ranged from simple dinners at home to full nights of dinner, dancing, and entertaining—sometimes until the early morning hours—so a Regency woman’s day did not necessarily end when the sun went down. Often, it was just getting started!

Please join me next month in Part 2 of this series as we explore the evening portion of a Regency woman’s day.

Food for thought: If you lived in Jane Austen’s time, what would you spend your time doing before breakfast?

Leave a Reply