Jane Austen never had children of her own, and she never wrote a conduct manual for mothers, but her novels certainly speak volumes about her opinion on the state of motherhood in 18th-century England—and specifically that of the landed gentry.

In her novels, the majority of Austen’s mothers can be broken down into three general categories: The Spectator, the Matchmaker, and the Manager.

The Indulgent Spectator

“Lady Bertram never thought of being useful to anybody.” –Mansfield Park

In this category, Austen presents us with lenient and uninvolved mothers like Lady Middleton, Lady Bertram, and Mrs. Price.

Lady Middleton

In Sense and Sensiblity, Lady Middleton is a mother described as having the “advantage of being able to spoil her children all the year round” (32). She insists on bringing her “troublesome boys” (55) with her to most of her social engagements, and their actions speak volumes: “Lady Middleton seemed to be roused to enjoyment only by the entrance of her four noisy children after dinner, who pulled her about, tore her clothes, and put an end to every kind of discourse except what related to themselves” (34).

Lady Bertram

In Mansfield Park, Austen says Lady Bertram is a mother who “might always be considered as only half-awake” (343). She is most often described as “indolent” (four times) and most often found sitting on the sofa (eight times). Lady Bertram spends “her days in sitting, nicely dressed, on a sofa, doing some long piece of needlework, of little use and no beauty, thinking more of her pug than her children, but very indulgent to the latter when it did not put herself to inconvenience” (19-20). As to the “education of her daughters,” she pays “not the smallest attention.” She is of little “service to her girls” in this regard, considering it “unnecessary” because they are “under the care of a governess, with proper masters, and could want nothing more” (20).

Mrs. Price

Lady Betram’s sister, Mrs. Price, is described similarly: “Her disposition was naturally easy and indolent, like Lady Bertram’s” (390). Upon visiting home, Fanny’s “disappointment in her mother was [great]; there she had hoped much, and found almost nothing” (389). In describing her home management, Austen says Mrs. Price’s days are “spent in a kind of slow bustle; all was busy without getting on, always behindhand and lamenting it, without altering her ways; wishing to be an economist, without contrivance or regularity; dissatisfied with her servants, without skill to make them better” (389). Mrs. Price, the mother of nine children, is termed “a partial, ill-judging parent, a dawdle, a slattern, who neither taught nor restrained her children, whose house was the scene of mismanagement and discomfort from beginning to end . . .” (390). With such an aunt and such a mother, it’s a wonder Fanny turns out so well.

The Meddling Matchmaker

“[T]he pains which they, their mothers (very clever women), as well as my dear aunt and myself, have taken to reason, coax, or trick [Henry] into marrying, is inconceivable!” –Mansfield Park

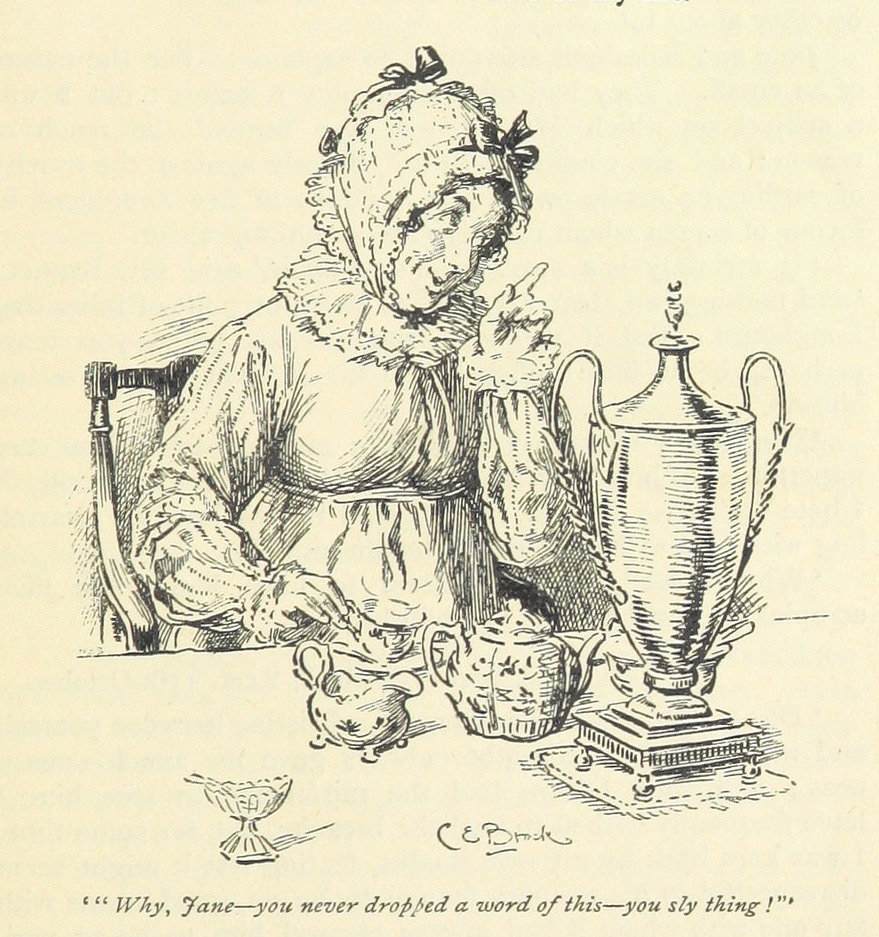

In this category, we find mothers like Mrs. Bennet and Mrs. Jennings who live to make matches. Both women make the business of matchmaking the main focus of their lives.

Mrs. Bennet

For Mrs. Bennet, marrying off her daughters is the “business of her life” (5). With five daughters and an entailed estate, Mrs. Bennet is always on the look-out: “A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!” (3-4). Mrs. Bennet even comes up with elaborate schemes to achieve her goal, such as the day when Jane is invited to Netherfield. Mrs. Bennet sends her off on horseback, in the hopes that it might rain and she might be asked to stay the night. It all goes according to plan: “This was a lucky idea of mine, indeed!” (31). Only when Jane and Elizabeth marry well does Mrs. Bennet finally experience the joyful relief of sweet success: “Happy for all her maternal feelings was the day on which Mrs. Bennet got rid of her two most deserving daughters” (385).

Mrs. Jennings

In Sense and Sensibility, Austen gives us this description of Mrs. Jennings: “She had only two daughters, both of whom she had lived to see respectably married, and she had now therefore nothing to do but to marry all the rest of the world” (36). In the role of matchmaking busybody, Mrs. Jennings is “zealously active.” Upon offering to take Elinor and Marianne to London, she says, “I have had such good luck in getting my own children off my hands that [your mother] will think me a very fit person to have the charge of you” (153). She takes her role as surrogate mother seriously while in London: “if I don’t get one of you at least well married before I have done with you, it shall not be my fault. I shall speak a good word for you to all the young men, you may depend upon it” (153-4).

The Business Manager

“She took the first opportunity of affronting her mother–in–law on the occasion, talking to her so expressively of her brother’s great expectations, of Mrs. Ferrars’s resolution that both her sons should marry well, and of the danger attending any young woman who attempted to draw him in.” –Sense and Sensibility

The mothers in this category, such as Lady Catherine de Bourgh and Mrs. Ferrars, possess money and power, and they use both to rule over their offspring. Lacking in motherly affection or compassion, their matchmaking is purely strategic.

Lady Catherine de Bourgh

Lady Catherine is “a tall, large woman, with strongly-marked features” (162), the only living parent of Miss de Bourgh, the heir to the de Bourgh estate. As Mr. Darcy’s aunt, and “almost the nearest relation he has in the world,” she believes she is “entitled to know all his dearest concerns” (354). With both Pemberley and Rosings at stake, she takes her role quite seriously. She believes it’s her duty to “unite the two estates” by ensuring the marriage of her daughter to Mr. Darcy (83). For this reason, upon hearing news of Mr. Darcy’s probable engagement to Elizabeth Bennet, Lady Catherine “instantly resolve[s] on setting off” to confront Elizabeth at Longbourn, that she “might make [her] sentiments known” and pressure Elizabeth into giving up Mr. Darcy (353).

Mrs. Ferrars

Similarly, Mrs. Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility is a “very headstrong proud woman” (148) who uses money to try to control her sons. In order to pressure Edward to marry well, she “told him she would settle on him the Norfolk estate, which, clear of land-tax, brings in a good thousand a-year; offered even, when matters grew desperate, to make it twelve hundred” (266). When he won’t comply, she threatens his ruin: “his own two thousand pounds she protested should be his all; she would never see him again; and so far would she be from affording him the smallest assistance, that if he were to enter into any profession with a view of better support, she would do all in her power to prevent him advancing in it” (267). Edward is “dismissed for ever from his mother’s notice” when he honors his engagement to Lucy. Mrs. Ferrars settles the estate, “which might have been Edward’s,” upon his brother Robert (268).

The Fond, Caring Mother

With only these examples of motherhood, one might think Austen had nothing good to say on the topic of mothers. Thankfully, Austen’s novels do provide us with redemptive motherly moments as well.

In Emma, Austen tells us that Miss Taylor “had fallen little short of a mother in affection” in her care of young Emma (5). In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Dashwood possesses “tender love for all her three children” (6). In Northanger Abbey, when Mrs. Morland worries that Catherine’s low spirits and inactivity stem from Catherine’s worldly experiences, she cautions her on that subject, saying, “there is a time for everything—a time for balls and plays, and a time for work. You have had a long run of amusement, and now you must try to be useful” (240). And Mrs. Gardiner is described in Pride and Prejudice as “an amiable, intelligent, elegant woman, and a great favourite with all her Longbourn nieces” (139). She gives mother-like advice to Elizabeth, “a wonderful instance of advice being given on such a point, without being resented” (145).

Mrs. Musgrove

In Persuasion, Austen presents a handsome picture of motherhood in Mrs. Musgrove. She loves her own children, worries that her grandchildren are being spoiled, and cares for the Harville children while Mrs. Harville nurses Louisa. At Christmas, the Musgroves bring the Harville children home with them and “receive their happy boys and girls from school” (129). Austen describes Mrs. Musgrove’s home at Christmas as “a fine family-piece.” There, Mrs. Musgrove is surrounded by “the little Harvilles,” a group of “chattering girls” at a table “cutting up silk and gold paper,” and “riotous boys” holding “high revel” near “tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies” (134).

Jane Bennet

Finally, Austen’s description of Jane Bennet’s natural motherly instincts gives us a glimpse into the future: “The children, two girls of six and eight years old, and two younger boys, were to be left under the particular care of their cousin Jane, who was the general favourite, and whose steady sense and sweetness of temper exactly adapted her for attending to them in every way—teaching them, playing with them, and loving them” (239).

On a day when we celebrate mothers everywhere, let us thank all of the mothers, grandmothers, aunts, sisters, and mentors who have guided and loved us through the various seasons of our lives.

You can follow more of my literary ramblings here on this site, over at Jane Austen’s World where I am a regular contributor, or on Instagram.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane, and R. W. Chapman. The Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen. Oxford UP, 1988.

Montaine

May 13, 2018 at 11:24 pmHello Rachel,

I have just discovered your blog. I am so glad, it is wonderful. Reading your article was a wonderful mother’s day gift. It made my day.

Thank you so much

Montaine

Rachel Dodge

May 14, 2018 at 11:44 amThank you, Montaine! That means so much. I’m glad you enjoyed it!